The Real Cost of Speaking Ill

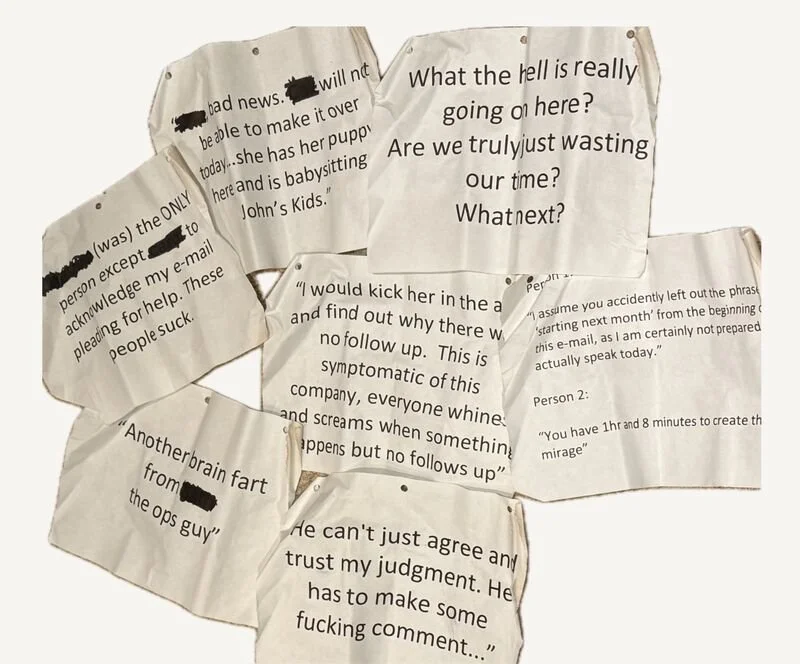

I came across this (somewhat ancient) set of printed emails recently — real messages from a team years ago, uncovered soon after a few of the authors had been asked to leave the company. What they wrote wasn’t criminal or perhaps even scandalous. It was something far more common: the quiet, corrosive habit of speaking ill of others.

“I would kick her in the ass…”

“These people suck.”

“Another brain fart from ___ the ops guy.”

“What the hell is going on here, anyway?”

You get the idea.

When these were discovered and shared with me, I didn’t feel angry. I felt a little betrayed, but not surprised. I felt more sad than anything else. Sad because our culture at that time wasn't what I told myself it was. Sad because in the end I was responsible as CEO. But maybe more so because I’ve been there too — venting behind closed doors or in text or Slack threads, assuming it’s a harmless release. Sometimes it even feels justified - almost wrong not to say anything. But what I’ve learned — and often the hard way — is that this kind of language doesn’t just chip away at the people you’re talking about. It chips away at you and everyone else involved.

It drains your energy.

It dulls your creativity.

It sabotages your company’s culture — and therefore, your own success within it.

It's easy to complain when things are chaotic, when information is scarce, when leadership feels absent, or when coworkers disappoint you. A lazy person can complain all day. The hard part — the real work — is staying constructive in the storm. It’s asking, “What can I do to try to make this better?” instead of “Who can I blame for this mess?” or "Not my problem."

Today, platforms like Blind and GlassDoor and even Google Reviews make it easier than ever to join the gripe-fest anonymously. But here’s the truth: the more time you spend in that state of mind, the less power you have to change anything. The less likely you will get where you really want to go. Complaining without action (and yes, action even if in the right can have consequences) creates a loop of helplessness. You start to believe the system is broken beyond repair — and soon enough, you’re part of why it is.

Positivity isn’t naïveté. It’s discipline. I took it for granted because I grew up in a family where anything was considered possible. My siblings and I, to a fault, believed we could make positive change.

But like anything else, a positive attitude takes practice. And I have found myself out of practice at times, which is a long slippery slope. When you practice positivity even in the most challenging circumstances, I believe the chances that life — and work — get substantially better increase significantly.